"The French Labor Code contains few provisions that apply specifically to women or men. Added to this is the lack of sex-disaggregated claims data, which helps to explain why the differentiated impact of work on the health of women and men has so far received little attention."[1].

Since 2014, the Labor Code has required employers to "assess the risks to the health and safety of workers [...] when fitting out or redesigning workplaces or facilities, organizing work and defining workstations. This risk assessment takes into account the differential impact of exposure to risk according to gender. " ( Article L. 4121-3 of the French Labour Code)

Noting the low level of implementation of this obligation, the Agence nationale pour l'amélioration des conditions de travail (Anact) has published a 78-page guide to help employers implement a differentiated approach to occupational risk assessment for women and men, embodied in the Document Unique d'Evaluation des Risques Professionnels (DUERP).

So how can we improve understanding and practical consideration of these different issues in risk assessment? This is the question that the guide published in September 2025 seeks to answer, through a pedagogical approach to understanding the issues at stake, a proposed methodology for relevant risk assessment, and a series of practical fact sheets.

---

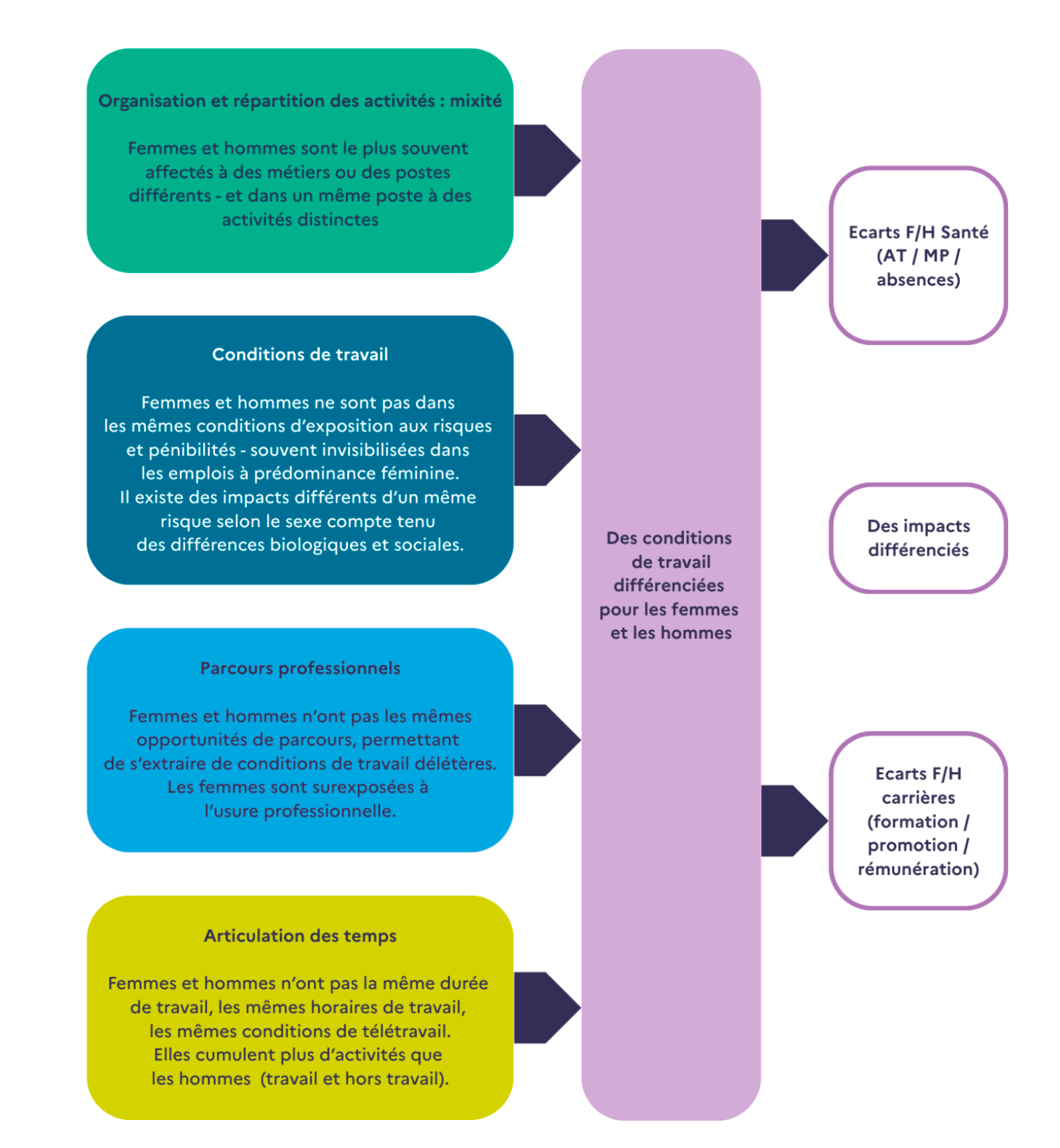

The guide shows first of all that there are two dimensions to take into account in order to better assess and prevent risks for women and men:

- the reality of women's and men's work, which is not the same, given different professions and career paths, as well as off-the-job activities - resulting in different levels of exposure to occupational hazards;

FOCUS : In most cases, women and men do not occupy the same positions. In female-dominated professions, the risks are often more invisible and therefore underestimated.

> Example: Exposure to the risks most frequently encountered in female-dominated professions (e.g. musculo-skeletal disorders, psycho-social risks, etc.) has a deferred impact. delayed impacts and are therefore less likely to be identified.

- the specific biological and social characteristics of women and men, which lead to different impacts of occupational hazards on their health.

FOCUS : The same exposure to one or more risks or work constraints may not have the same effects on the health of women and men, due to biological or social differences.

> Example: differentiated impact of chemical agents, carrying loads, etc., impact of atypical working hours, impact of management under pressure, etc.

The guide is divided into 3 main sections:

1. Health and working conditions for women and men: the relevance of a differentiated approach

The first part of the guide explains the differences in claims rates, exposure to the risks of arduous work, professions and career paths, social differences and factors of invisibility, all of which have been highlighted by research carried out over many years.

The first observation is that, " in the majority of cases, occupational health policies and prevention practices are built on a model of gender-neutral workers, whose implicit referent is the male worker "[2].

FOCUS : The overall decrease in the number of occupational injuries (OI) of 11.1% between 2001 and 2019 actually corresponds to a decrease of 27.2% for the male population and an increase of 41.6% for the female population[3].

> Example: In female-dominated service professions (care, cleaning, teaching, retail, catering, etc.), employees are exposed to 7 out of 8 occupational risks (physical hardship, lack of support, value conflicts, lack of autonomy, emotional demands, job instability, organizational constraints) - whereas male-dominated blue-collar professions are exposed to 4 out of 8 risks (physical hardship, work intensity, lack of support, lack of autonomy).

Anact's Égalité Santé model "All other things being equal".

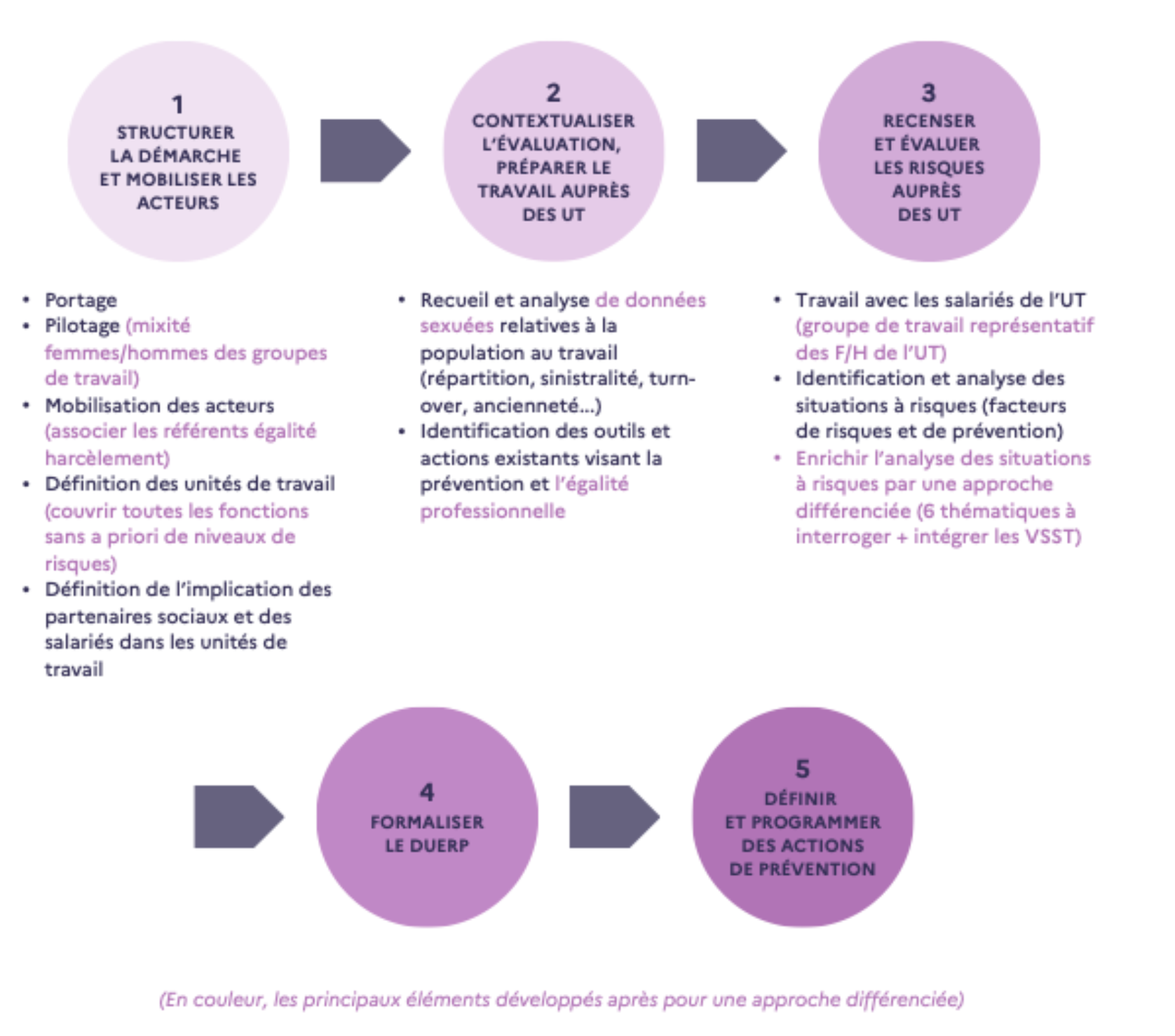

2. Steps and methodological principles for a differentiated assessment of occupational risks

The guide notes that most risk assessment methods are structured around these 5 main phases. It then proposes a number of enhancements to take account of the differentiated approach to each of these 5 stages in the analysis process.

An example of a DUERP is then proposed to give concrete expression to the inclusion of these elements. Finally, we look at how to draw up a program for the prevention of occupational risks and improvement of working conditions (PAPRIPACT, see https://www.tennaxia.com/blog/papripact-que-dit-la-reglementation) or, in companies with fewer than 50 employees, a list of preventive actions. Circular no. 6 DRT of April 18, 2001 reminds us that " risk assessment is not an end in itself" , and that the DUERP must contribute to the development of the program. It envisages the possibility of labor inspectors noting the absence of any use of DUERP data in drawing up this program[1].

3. Practical data sheets for questioning gender-differentiated risk exposure and impact in the DUERP

" Penser la santé au travail au féminin : différencier n'est pas discriminer "[2] (Thinking about women's occupational health: differentiation is not discrimination )

The third part of the guide proposes 25 questions to check that the differentiated approach has been taken into account in the various stages of risk assessment.

Example: Is the DUERP regularly updated to incorporate new risk situations identified? Are the measures put in place evaluated with the involvement of the men and women concerned, to check their effectiveness?

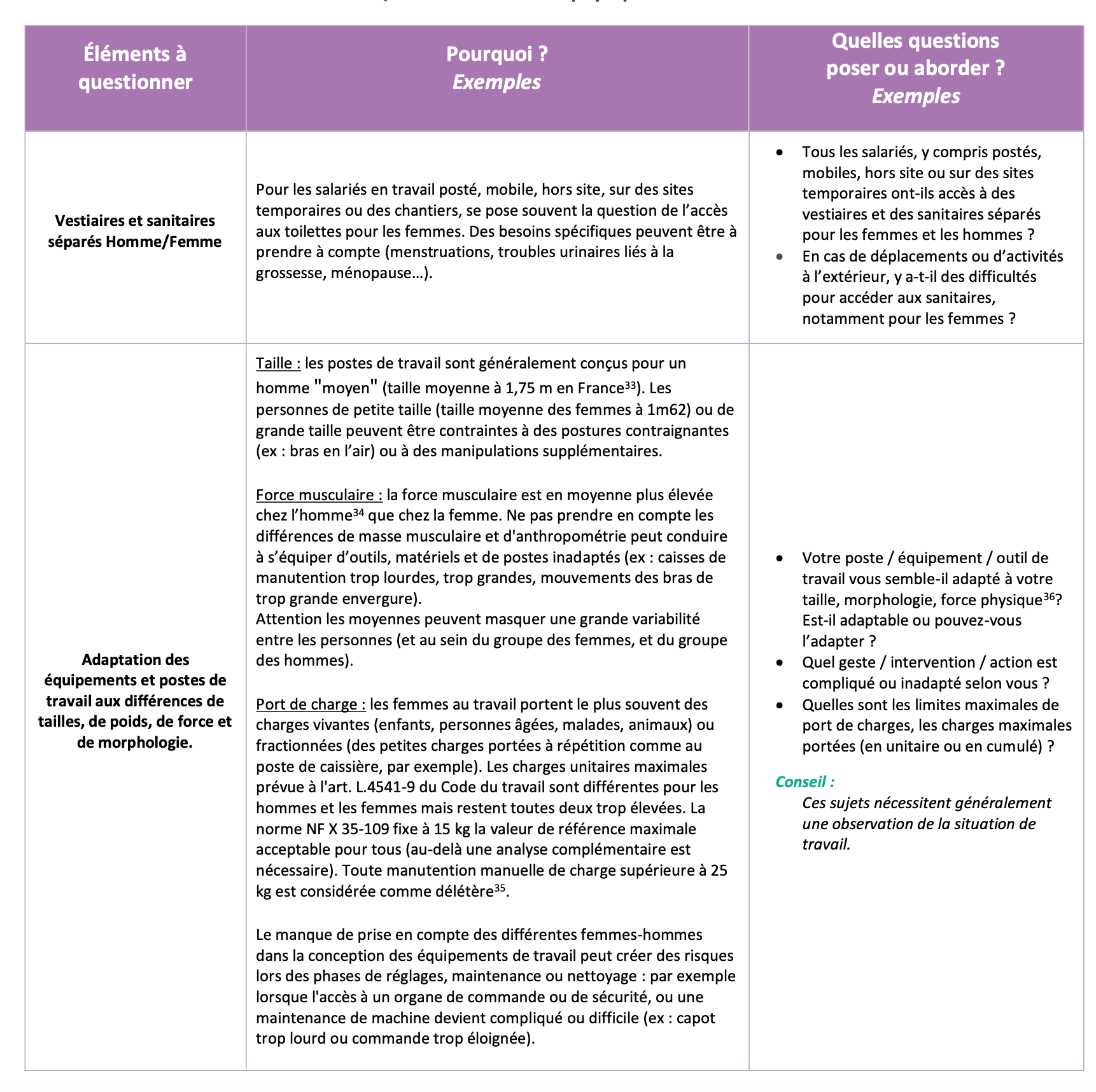

The guide also includes a table containing a series of questions to be asked in order to enrich the risk assessment process. These questions concern the following topics:

- Physical work environment (e.g. adapting equipment and workstations to differences in height, weight, strength and morphology)

- Work organization and processes (e.g. organizational constraints: working in a hurry, under pressure...)

- Time organization and coordination (e.g. work/life balance)

- Workplace relations and management (e.g. relations in gender-diverse workgroups)

- Career paths and skills (e.g.: more limited career development prospects for women, which accentuates the phenomenon of professional attrition).

- Risks affecting the reproductive health of women and men (e.g. maternity and breastfeeding situations)

Example for the first theme:

To remember:

- There is a legal requirement for gender-differentiated assessment of occupational risks. This requirement presents practical difficulties in its implementation, and has not been widely deployed in companies since its introduction in the Labor Code.

- Women and men are exposed to different levels of risk (different work realities) and the impact on their health is different (gender-specific).

- Differentiated consideration of occupational risks for women and men is possible thanks to a concrete methodology, implemented throughout the various stages of risk assessment (the guide offers keys to success in these different stages).

- The DUERP is not an end in itself, but rather the basis for a concrete program of preventive actions (the guide suggests a series of questions to ask in order to ensure that the differences between men and women in work situations are properly taken into account).

[1] Extract from the Anact guide, September 2025, page 2.

[2] The Brussels-based organization ETUI has been pointing this out since 2003, with Laurent Vogel. Extract from the Anact guide, September 2025, page 8.

[3] Extract from the Anact guide, September 2025, page 9.

[4] Extract from the Anact guide, September 2025, page 22.

[5] Senate report "Santé des femmes au travail : des maux invisibles" - 2023 mentioned in the Anact guide, September 2025, page 4.

.svg)

.jpg)